Sword Guard with Plum Blossoms and Snowflakes

Yushusha Isshi, Japan

Edo period, 1800s

2.938 in x 2.625 in

In celebration of Isabel Marie Conversano Seibert by Elizabeth P. Seibert, 1997.16

Photograph © Denver Art Museum 2011. All Rights Reserved.

This sword guard—called a tsuba [SUE-bah]—was made by Yushusha Isshi [you-SHOO-shah EE-she] during Japan’s Edo period. At the age of 15, Isshi became part of the Goto school. When a craftsman became a part of a “school” like the Goto school, it meant that he was trained by craftsmen who had experience creating pieces in the style of the Goto family. As the official group of craftsmen to the most powerful samurai leader in Japan, the Goto family made various items that were part of a properly outfitted sword, including sword guards. Under the guidance of Goto Ichijo [GO-toe ee-CHEE-joe], who is considered the last great craftsman of the Goto family, Isshi learned the Goto family’s secrets to working with metal and helped the head of the school craft pieces for customers.

Sword guards were originally made by the same artisans who made sword blades, but by the Edo period, many of the pieces that accompanied the blade were made by a separate specialist or group of specialists. By the time these sword guards were made, Isshi had mastered the ability to work with different metals and combine them in a single object. He used an inlay technique to create this sword guard, which involves embedding a soft metal, like gold or silver, into a harder metal. His skill at working on a small scale is evident in the details seen on this sword guard.

Sword guards served as both functional and decorative items. They were initially created to be hand guards that separated the blade of a sword from the handle. A sword guard prevented the warrior’s hand from sliding onto his blade as he thrust his sword forward. It also could protect his hand from an enemy’s sword .The guard also balanced the sword’s center of gravity and gave the warrior greater control over his weapon.

The Edo period (1603–1868), when this sword guard was made, was largely a time of peace. During this time sword guards became much more ornamental as opposed to functional. Artisans developed new styles of carving and inlay, and used special materials like gold, which was less practical than the iron that was used previously because it is a softer metal. The guards were often the most decorative part of a sword and reflected changes in fashion. Expensive and beautiful sword guards showed wealth and good taste. A samurai warrior often owned several sword guards and would change them, along with the other fittings, based on the occasion. He wore his sword with the guard placed at the center of his body, making it visible to others.

This sword guard is decorated with flower blossoms on one side and snowflakes on the other. Falling blossoms shown at the end of their life are often a symbol of what the Japanese call mono no aware [MOE-no no ah-WAR-ay], which means “the sadness of things.” This concept indicates a sensitivity to the fleeting nature of beauty. The short life of the blossoms has often been associated with mortality, and is sometimes thought to mirror the life of a samurai warrior. The snowflakes may be another reference to something that lasts only a short time.

A sword guard is part of a sword’s fittings. The fittings included the hilt (handle), the scabbard (blade cover), the tsuba (sword guard), and menuki (grip enhancers).

A diagram of a samurai sword’s fittings:

Samurai Sword Fittings Diagram

Another sword guard in the Denver Art Museum’s collection:

Sword Guard of Bamboo and Tiger

Two examples of grip enhancers in the Denver Art Museum’s collection:

Details

Flowers

The flowers could be either plum or cherry blossoms. Both types of blossoms are significant in Japanese culture. Plum blossoms are associated with the start of spring and often serve as a protective charm against evil. They are traditionally planted in the northeast portion of a Japanese garden because that is the direction from which evil is believed to come. The Japanese eat pickled plum to prevent misfortune. The cherry blossom is the national flower of Japan. Though the blossoms are no more beautiful than those of other flowering trees, they are highly valued because they usually disappear within a week of first blooming. They are often seen as a symbol of the ephemeral nature of life and are frequently depicted in art. They are an omen of good fortune and represent love and affection.

Falling Petals

Four single petals seem to float randomly around the blossoms. Imagine how easy it is for the slightest breeze to tear a delicate petal from a flower and carry it away. These falling petals emphasize the short life of the blossoms.

Snowflakes

Snowflakes do appear in Japanese art, but not as often as flower blossoms. Using an inlay technique, Isshi embedded silver to create the snowflakes on this sword guard. They are similar to real snowflakes in that they all have six arms and are all unique. However, the arms of a real snowflake are all about the same length, while the arms of the snowflakes on the sword guard differ in length. This causes us to wonder: Did the artist actually examine real snowflakes when making this sword guard? We are not sure how to answer this question because although some characteristics of a real snowflake are portrayed correctly, others are not.

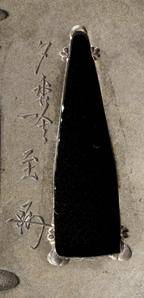

Signature

You can see the signature of the artist on the side with the flowers. The artist made the signature by cutting into the metal—a technique called incising. In many cases, the side with the signature is considered to be the front of the sword guard. The front faces away from the warrior carrying the sword; it is the side that others see.

Metal

The body of this sword guard is made from shibuichi [she-boo-EE-chee], which is an alloy (mixture) made of 75% copper and 25% silver. It is sometimes called “dusky silver” because it is not as shiny or bright as pure silver. If you look carefully you can see that some parts of the snowflakes and blossoms are brighter, which may mean a more pure form of silver was added to the surface of the dusky silver in these areas.

Gold

Gold is used to form the stem of the two-blossom group as well as the centers of the flowers. There are tiny gold dots that look like gold dust scattered around the flowers on one side and around the snowflakes on the other. The broken clouds on the side with the blossoms reveal a crescent moon that is also made of gold. Gold is not very durable, so seeing it here tells us that this sword guard was made to be used during times of peace, almost as a piece of jewelry, rather than as a functional hand protector.

Shape

Sword guards can be any number of shapes, but they are usually round or oval. This sword guard is not quite oval; its edge is somewhat wavy, creating four lobes or projections.

More Resources

Japanese Legend of "Winning Without Hands"

A storyteller from the Asian Art Museum tells the story of the famous samurai Bokuden.

Websites

Japanese Sword Mountings (Tsuba)

Wikipedia overview of sword guards (Tsuba, Japanese word) in Japanese history.

Relationship of Sword Guard and Sword

Describes the use of sword guards and their Yin/Yang relationship.

Edo Period Timeline

An overview of the Edo Period timeline from the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Seasons in Japanese Art

Information from an exhibition, "Seasons: The Beauty of Transience in Japanese Art," from the Art Gallery of New South Wales.

The National Consortium for Teaching About Asia

A web resource for elementary and secondary teachers

Denver Art Museum, Asian Art

Denver Art Museum Asian Art Web Page

Denver Art Museum Wacky Kids

Denver Art Museum Web Page, Kids Books about Japan

Cherry Blossom Popcorn Tree

Pre-K to 1st grade art project

Books

Kuniyoshi, Utagawa. 101 Great Samurai Prints. Mineola, NY: Dover Publications, 2008.

A full color book of wood-block prints of samurais with an overview of their portrayal in Japanese illustrations and art.

Reeve, John. Japanese Art: In Detail. London: British Museum Press, 2005.

Arranged thematically, the book includes chapters on nature and pleasure, landscape and beauty, all frames by the themes of serenity and turmoil, the two poles of Japanese culture, ancient and modern. Highlighting, close up and in color, examples of design and craft in prints, paintings and screens, metalwork, ceramics, wood, stone, and lacquer.

Mason, Penelope. History of Japanese Art. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall, 2004.

A comprehensive, extensively-illustrated, detailed overview of Japanese art -- from the Joman period (10,500 B.C.E. to 300 B.C.E.) through World War II.

Guth, Christine. Art of Edo Japan: The Artist and the City 1615-1868. New York : H.N. Abrams, 1996.

This beautifully illustrated book examines the art and artists of the Edo period, one of the great epochs in Japanese art. Together with the imperial city of Kyoto and the port cities of Osaka and Nagasaki, the splendid capital city of Edo (now Tokyo) nurtured a magnificent tradition of painting, calligraphy, printmaking, ceramics, architecture, textile work, and lacquer.

Patt, Judith, and Barry Till. Haiku: Japanese Art and Poetry. California: Pomegranate, 2010.

Haiku: Japanese Art and Poetry presents thirty-five pairs of poems and images, organized seasonally. The Introduction details the origin and development of haiku, the lives of the most famous poets.

Children’s Books

Doran, Claire, and Andrew Haslam. Old Japan. CENGAGE Learning, 1995.

Practical role-play and activities, based on the lifestyles of ancient peoples, are combined with a sensitive and wide-ranging text to create a stimulating experience of Japanese history. Includes section on kendo (the way of the sword).

McCarthy, Ralph F. The Inch-High Samurai. Kodansha International, 2001.

A Japanese fairy tale of a boy named Inchy Bo, the Japanese cousin of Tom Thumb and Thumbelina.

Donegan, Patricia. Haiku (Asian Arts and Crafts For Creative Kids). Boston: Tuttle Publishing, 2003.

This book introduces five styles of haiku to readers. It includes the following projects for elementary age children: your first haiku; your favorite season; your own personal haiku; haiku with pictures; and haiku with a friend.

Funding for object education resources provided by a grant from the Morgridge Family Foundation. Additional funding provided by the William Randolph Hearst Endowment for Education Programs, and Xcel Energy Foundation. We thank our colleagues at the University of Denver Morgridge College of Education.

The images on this page are intended for classroom use only and may not be reproduced for other reasons without the permission of the Denver Art Museum. This object may not currently be on display at the museum.