Jar

- Isadora Medina, Zia, American, 1894-1951

- Born: Zia pueblo

- Work Locations: Zia pueblo

- Active Dates: 1910-?

Isadora Medina was born around 1850–55 and died in 1951. Little is known about this Zia Pueblo artist, and this is the only known pot with her signature.

Historically, Zia Pueblo pottery, similar to other Pueblo pottery, was used to store food, hold water, and serve meals. Pottery was also valuable for trade. Members of the Zia Pueblo today credit the women of Zia for saving the pueblo during the bleak years of the early 1900s by trading pottery for food and other essentials. Prior to about 1940, only Zia women made pottery, although men contributed as painters. Today some Zia men are potters.

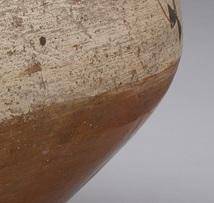

Much about this jar is traditional—its construction using the coil method; the olla shape, with its nearly spherical body and short vertical neck; the red, cream, and black colors; and the bird motif—but the artist added her own creative stamp. Although the bird looks like a Zia roadrunner, its segmented body is reminiscent of an Egyptian bird. The discovery of King Tutankhamen’s tomb in 1922 dominated international news, and it’s possible that Isadora Medina drew inspiration for her bird design from photos of this event. Though we can’t be sure about this, the piece is unique in its decoration among Pueblo pottery in general, and among Zia pottery in particular.

Details

Red Underbelly & White Body

The red underbelly is characteristic of Zia pottery. The red color comes from naturally occurring iron oxide in the clay. Medina applied watered-down clay, called slip, to the surface of the vessel before firing it. Then she hand-polished the surface with a burnishing stone so it would appear semi-glossy after firing. On the upper portion of the jar, Medina used a cream-colored slip. This, too, would have been hand-burnished before firing.

Shape

Zia potters are masters at making large vessels by hand. Medina shaped her pot using the coil method. After mixing powdered clay with water and temper (a material used to improve the plasticity of the clay; in Zia, typically crushed basalt from a nearby mesa), she pressed the clay into a small mold to form the base of the jar and began adding coils of clay to enlarge the jar. Then she pinched, smoothed, and burnished the surface before firing. Certain details of construction are practically unique to Zia. For example, Zia potters add a coil to the outside surface of the preceding coil when building a vessel. At other pueblos, potters usually add coils to the inside.

Zia Bird

Beginning in the early 1820s, “realistic” bird motifs began appearing in Zia pottery, probably as a response to tourist preferences. Zia artists have identified these birds as parrots, raptors, swallows, and roadrunners, to name a few. Medina’s bird most closely resembles the roadrunner, which is sacred to the Zias and is also the state bird of New Mexico. However, Medina chose to segment the wings and tail feathers of her bird, similar to how Egyptians depicted feathers, leading to speculation that she may have been inspired by photos she saw from King Tutankhamen’s tomb.

More Resources

Websites

New Mexico Office of the State Historian: Zia Pueblo

Video on Zia pueblo and the Zia’s relationship with the Sun.

Zia Pueblo

Information on Zia Pueblo and Zia pottery.

Native Americans Encyclopedia

A book online that covers many American Indian Tribes, Zia can be found starting on page 139

Indian Pueblo Cultural Center

Learn valuable information about the Zia Pueblo , where it is located and cultural traditions.

Books

Caraway, Caren. Southwest Indian Designs. Stemmer House Publishers, 1983.

A brief history of Zia and a general description of a few Zia Pottery designs can be found under the Zia section.

Funding for object education resources provided by a grant from the Morgridge Family Foundation. Additional funding provided by the William Randolph Hearst Endowment for Education Programs, and Xcel Energy Foundation. We thank our colleagues at the University of Denver Morgridge College of Education.

The images on this page are intended for classroom use only and may not be reproduced for other reasons without the permission of the Denver Art Museum. This object may not currently be on display at the museum.