Students will observe and discuss Hubert Candelario's Jar and then create a sequenced narrative of events about a familiar process. Students will check each other’s stories for missing information, or "holes," in the story.

Students will be able to:

- use context to confirm or self-correct word choice, rereading as necessary;

- identify real-life connections between words and their use;

- create a beginning, middle, and end of an event sequence;

- proofread other students' stories; and

- work collaboratively to identify missing information.

Lesson

- Ask students if they have ever heard the phrase, “There are holes in your story.” Or, “Your story just doesn’t add up.” What do those phrases mean? Have a few students offer ideas or hypotheses of what they think these phrases might mean and why they think that.

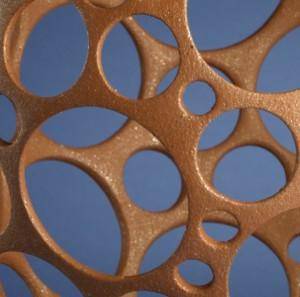

- Show students the image of Hubert Candelario's Jar but don’t tell them the title or what the object is. Ask them to tell you what they think it is. What do they think it is made out of? Why do they think this? Does it have a purpose? What do they think its purpose is? Why do they think this? Is it hard to tell what it is with so much missing? What do they think it looked like with all of the holes filled in?

- Tell students what the object is. Share with them information from the About the Art section and talk about how Candelario creates these jars. Talk about the process he goes through of allowing the clay to dry slowly, cutting holes from the top, and then turning the jar over and cutting holes in the bottom. If it cracks or crumbles, if there are too many holes or they are in the wrong places, he starts the whole thing over again.

- Ask the students to write a short story about how they get ready for school in the morning or the routine the class follows when they start the school day, or something else that would be familiar to most of the students. Then they will work in pairs and share their stories with each other. Working together, the students can decide if there are any holes in their stories. Did they leave anything out that is needed to hold the narrative together? Each student will revise their own story, filling in any holes.

- Older students might then take out key pieces of information and share their stories with a different partner. The partner could try to fill in the holes with what they think is missing.

- Younger students could draw the steps of their story and follow the same process. Or students still in the pre-writing stage could dictate their story to an adult who could write it for them, and they could then trace the letters with their pencil to practice writing the words.

Materials

- About the Art section on Hubert Candelario's Jar (included with the lesson plan) or student access to this part of Creativity Resource online

- Color copies of Hubert Candelario's Jar or the ability to project the image onto a wall or screen

- Paper for writing sequenced narrative or drawing

- Pencils, crayons, color pencils, or other art media, or access to a word processor

Standards

- Social Studies

- History

- Geography

- Understand chronological order of events

- Understand people and their relationship with geography and their environment

- Visual Arts

- Invent and Discover to Create

- Observe and Learn to Comprehend

- Relate and Connect to Transfer

- Envision and Critique to Reflect

- Language Arts

- Oral Expression and Listening

- Research and Reasoning

- Writing and Composition

- Reading for All Purposes

- Collaboration

- Critical Thinking & Reasoning

- Information Literacy

- Invention

- Self-Direction

Jar

Hubert Candelario, United States

1997

Height: 11.25 in. Width: 8.25 in.

Denver Art Museum Collection: Gift of Virginia Vogel Mattern, 2003.1034

Photograph © Denver Art Museum 2009. All Rights Reserved.

“There are only four potters at San Felipe Pueblo,” says Hubert Candelario, “and I’m one. The other three are married to potters from other pueblos, and that’s how they learned. Me? I just had a feel for it.”

Hubert Candelario was born in 1965 in Albuquerque, New Mexico. Before becoming a professional artist, he studied architectural drafting and design at the Pheonix Institute of Technology in Arizona. In the 1980s he developed an interest in clay and began experimenting with pottery techniques and form. He was inspired by the work of Maria Martinez (whose work is also on the Creativity Resource website) and was fascinated by ancient Pueblo pottery designs. Because there are very few potters from San Felipe Pueblo, Candelario did not learn techniques from others, but experimented with his own personal style. “As a contemporary Native American Indian potter I have no limits, only choices,” he says. Today, Candelario lives in Albuquerque where he works on his pottery full-time.

After learning the basic techniques used to create a piece of pottery, Candelario used his experience in structure and design to move beyond the boundaries of traditional pottery. When speaking about a similar “Holey Pot” Candelario said, “I have always loved structure and design, fields that I originally studied at school. While making this pot, I thought about ways to incorporate structural principles into the design. I began cutting away holes in a traditional pot to see how far I could push the limits of structure. It was a technical challenge that succeeded.”

Details

Shimmer

The clay and slip that Candelario uses contain gold colored flakes of mica that give the finished pot a glowing and sparkling surface.

Round Holes

Perfectly round holes pierce the jar on all sides. According to Candelario, “the holes are like nature; they are the structure of cells.” He first forms the jar by using a traditional method of coiling clay from a bowl base. After letting the clay dry for a few days, he uses a circular template to draw circles and then carves the holes using an Xacto knife. He carves the bottom of the pot first, then turns it over and carves the top. If cracks occur at any point, he will start over from the beginning.

Funding for object education resources provided by a grant from the Morgridge Family Foundation. Additional funding provided by the William Randolph Hearst Endowment for Education Programs, and Xcel Energy Foundation. We thank our colleagues at the University of Denver Morgridge College of Education.

The images on this page are intended for classroom use only and may not be reproduced for other reasons without the permission of the Denver Art Museum. This object may not currently be on display at the museum.