Students will start by exploring the ways in which architect Daniel Libeskind broke boundaries when designing the Frederic C. Hamilton Building. They will engage in a series of creativity exercises designed to enhance their understanding of critical thinking and problem solving.

Students will be able to:

- describe barriers to creative thinking and at least two strategies for overcoming these barriers;

- describe how using their senses and exploring the creativity of others can expand the ideas and vocabulary of their writing;

- use a variety of devices to convey meaning; and

- critique the aesthetic value of their work and that of their peers.

Lesson

Day 1

- Have the students get into groups of three to four.

- Share the following quotation from French philosopher Emilé Chartier: “Nothing is more dangerous than an idea when it’s the only one you have.” Ask each group to try to come up with at least two ideas about what this quotation means, then call on a couple of groups to share. So often in our daily lives what we do requires habit more than creative thought. Sometimes, however, creativity is needed to complete a task or solve a problem; other times it’s just fun to think in different ways. Share that today you are going to help them learn to tap into different ways of thinking.

- Give each group a creativity bag and ask them to come up with at least three uses for each object that has nothing to do with its everyday purpose. It may help to imagine what the objects could be if they were five inches tall or from another planet. Note: Set the norm that no idea is “stupid,” and that during brainstorming every idea should be written down, no matter how farfetched.

- Call on each group to share their favorite idea for each object.

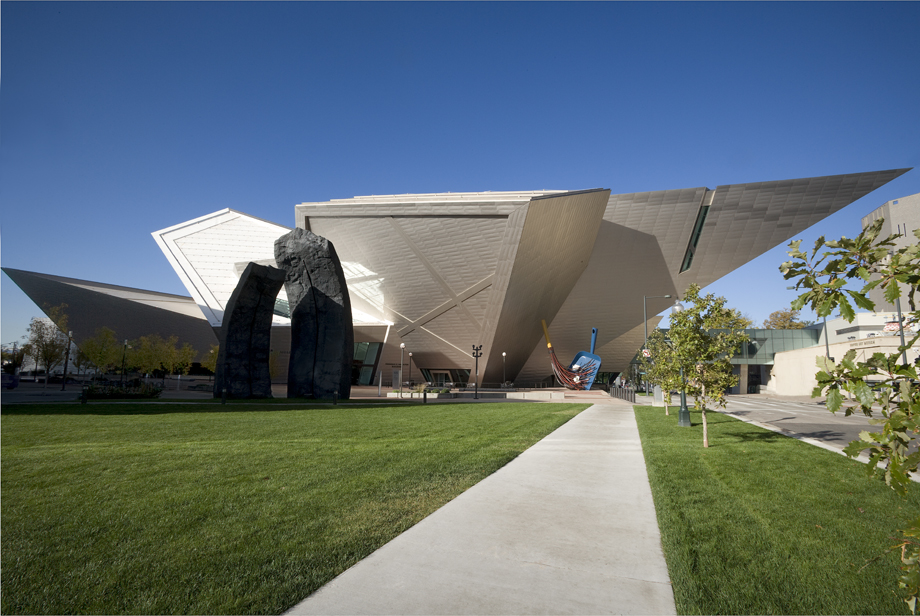

- Distribute the picture of the Frederic C. Hamilton Building. Ask the groups to talk about and write down at least five ways that the architect broke traditional boundaries. You may have the groups share ideas with the class. You may want to use the About the Art section to highlight information related to the students’ discussion.

- Leave time to clean up.

Day 2 (or continued block period)

- Have the groups summarize what the lesson has taught them about creativity so far.

- Let students know that creativity works best when connecting to multiple senses. Pass out the oranges and cloves and ask the students to push the cloves into the oranges to help inspire their writing.

- Pass out the handouts. Using the Frederic C. Hamilton Building and the orange as inspiration, have the students complete the writing exercises. Encourage them to have fun and take risks.

- If you could hear the building, what would it sound like?

- If you could give the building a smell, how would you describe it? Compare the smell of the orange with cloves to the smell of the building. How are they the same? How are they different?

- What do you see? What in nature compares to what you see in the building? How?

- Compare the texture of the orange to the texture of the building. How could the words you use tell the reader what each object is without directly stating it?

- If the orange had the power to defy gravity and could roll all over the building, what might it feel on its journey?

- If you could take a bite out of the building, how would it taste? If you imagined it wasn’t metal but really a type of food, what would it taste like now, and what would it feel like in your mouth?

- Have the students get back into the same groups for a critique. Have each student share two of their favorite answers with the group. Encourage the group to use the questions below to push each other to create more powerful and vivid writing. Make sure students understand the importance of being both truthful and kind in their criticism.

- Could you sense what the person writing was trying to help you sense? (Whether hearing, smelling, touching, etc.)

- Did the writing move you? Did it evoke an emotional reaction within you?

- Were the words and overall presentation of the answer pleasing to you?

- Lead a large-group discussion to bring closure to the activity. Have the students write down their answers first (Write It Before You Talk), and then ask volunteers to share their responses.

- If you had written about the building without doing any of the creativity exercises, how would the activity have been different?

- How did having to use your senses challenge you and your writing?

- What next? How can you use these skills to help you think more creatively in writing, history, science, or even in relationships with your friends and family?

Materials

- One creativity bag for every three to four students: one snack-size Ziploc bag containing one paper clip, one Q-tip, one popsicle stick, and one bottle cap (or four other common items)

- One orange per student

- One box of whole cloves for every three to four students

- Paper and writing utensils per student

- About the Art section on Daniel Libeskind and the Frederic C. Hamilton Building

- One color photocopy of the Frederic C. Hamilton Building for every three children or a computer able to project a picture of the building on a wall or screen

- The Hamilton Building Writing Activity

Standards

- Visual Arts

- Invent and Discover to Create

- Observe and Learn to Comprehend

- Relate and Connect to Transfer

- Envision and Critique to Reflect

- Language Arts

- Oral Expression and Listening

- Research and Reasoning

- Writing and Composition

- Reading for All Purposes

- Collaboration

- Critical Thinking & Reasoning

- Information Literacy

- Invention

- Self-Direction

Frederic C. Hamilton Building

Daniel Libeskind and Davis Partnership Architects, United States

2006

146,000 sq. ft.

Photo by Jeff Wells, Courtesy of the Denver Art Museum

Photograph © Denver Art Museum 2009. All Rights Reserved.

Architect Daniel Libeskind worked with Denver-based Davis Partnership Architects to design the Denver Art Museum’s Frederic C. Hamilton Building.

Libeskind was born in Poland in 1946, the son of two Holocaust survivors. At the age of eleven, he immigrated to Israel with his parents, where his family lived for two years before they left for New York. Libeskind was one of the last immigrants to arrive by boat through Ellis Island and he became an American citizen in 1965.

As a child Libeskind was a musical prodigy, winning international competitions with his performances on the accordion. He left music to study architecture at New York’s Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art, followed by graduate work at Essex University in England. He went on to work as a professor and theorist before completing his first commission, Berlin’s Jewish Museum, at the age of fifty-two.

The Denver Art Museum’s Hamilton Building is Libeskind’s first completed building in the United States. He was also chosen as the master plan architect for the World Trade Center site in New York City.

In 1999, museum director Lewis Sharp and then-mayor Wellington Webb decided it was time for the museum to expand. A new building would allow the DAM to display more of its world-class collection and provide the space needed to host major traveling exhibitions.

With the Hamilton Building, Daniel Libeskind continued a tradition of bold architecture that began with Gio Ponti’s North Building. Libeskind tells us that he was inspired by the “craggy cliffs of the Rockies” and by his experiences in Denver. He describes Denver as “a dynamic place, the people are dynamic. And that is part of the composition of the building.” The lively architecture signals to the public that new things are going on inside; the experience begins before one even enters the DAM.

Details

Titanium

Libeskind chose to complement Gio Ponti’s million gray glass tiles of the North Building by selecting another reflective and unusual material: 9,000 titanium panels. Libeskind said, “We had an aim from the beginning: a building that is luminous.” The Hamilton Building’s different sides reflect light at different angles, and thus appear to be different shades of gray. The titanium also reflects varying colors throughout the day. It often appears more rosy in the early morning hours and golden at sunset, depending on the weather.

Fun Fact: 9,000 titanium panels cover the building’s surface.

The Prow

The tip of the building, which we call the “prow,” makes a reaching gesture across 13th Avenue toward the North Building and Civic Center. The angled walls of the prow, and the many other angled walls that shape the building, are reflected inside and create unique interior spaces. These dramatic spaces have provided new opportunities for innovative displays of artwork.

The Atrium

Libeskind spoke of the atrium as an introduction to the visitor’s experience of the building: “The first sounds, the atmosphere, the connectivity with that atmosphere—the mood is set. And I think it’s proper that an atrium should set those moods because that’s where you quite literally enter, get informed, get ready for an adventure with art.” The walls and ceiling of the atrium create a variety of shaped spaces, making it one of the most dramatic spaces in the building.

How Does the Building Stay Up?

The building is essentially a giant truss, meaning its steel frame is a balanced network of interlocking triangles. After all the steel beams are set in place, the building holds itself up and transfers weight to “anchors” of concrete pillars that reach down into bedrock. Libeskind described the building as a tree, branching out from these anchoring “roots.”

Fun Fact: 2,750 tons of steel and 50,000 steel bolts were used in the Hamilton Building.

Funding for object education resources provided by a grant from the Morgridge Family Foundation. Additional funding provided by the William Randolph Hearst Endowment for Education Programs, and Xcel Energy Foundation. We thank our colleagues at the University of Denver Morgridge College of Education.

The images on this page are intended for classroom use only and may not be reproduced for other reasons without the permission of the Denver Art Museum. This object may not currently be on display at the museum.