Students will critically examine and discuss Our Lady of the Victory of Málaga, paying particular attention to the elaborate detail. Students will divide into two or three groups and each group will write a descriptive analysis of the work of art using a roulette writing technique.

Students will be able to:

- describe and interpret what they see in the image of Our Lady of the Victory of Málaga;

- imagine what Our Lady of the Victory of Málaga might have looked like without such detail;

- recognize the importance of detail in allowing a reader to visualize an image; and

- create a descriptive sentence regarding the image that will become part of a collaborative piece of writing.

Lesson

- Show students the image of Our Lady of the Victory of Málaga. Ask students to describe what they see and make predictions of what they think the image might be of.

- Share the information from the About the Art sheet. Go over the “Things to Look For” information. Then in groups or as a whole class, re-examine the image. Make sure students can clearly see all of the special details. Treat the image like a scavenger hunt where students find the hidden clues in the artwork. What symbols are used and what do they mean? Have students find symbols from the New World cultures of Peru and Bolivia as well as the Old World cultures of Spain and other countries in Europe. Don’t forget to find details hidden in the ornate decorative work and in the bottom section of the painting.

- Point out how the elaborate and fancy detail found in the painting adds meaning and interest to the painting. What would this look like if the woman was wearing a simple brown dress with no detail and she was sitting in a black room? Would we know much about the story?

- Explain that writing relies on detailed descriptions as much as paintings rely on visual details. Like the elaborate detail in this painting, the more figurative and detailed language that a writer uses, the more interesting the writing.

- Divide the class into groups of two or three depending on size. Each group needs access to a good color image of Our Lady of the Victory of Málaga.

- Explain that the groups are going to do a group roulette writing. One person will start by writing a sentence, then pass it around to the next person who adds another sentence, and so on until it has gone around enough times that there is nothing left to write about.

- Each person will write a sentence describing and adding to the story of the painting. Remind students to use lots of sensory details (how things feel, sound, look, smell, and possibly taste). Older students may also want to use figurative language where they compare and contrast what they see to other things.

- Each student should pay attention to standard English conventions as is appropriate to age and ability level of the individual. However, groups should be accepting of everyone and realize there is no wrong answer here – this is just a fun way to play with language.

- After groups are finished, have one person read their writing out loud while others close their eyes and try to picture the image. How close did they get to describing the real thing? What language could have been added to make the writing more effective? What parts were really descriptive?

Materials

- Lined paper to write on

- Variety of pencils or other writing implements

- Copies of About the Art sheet on the Our Lady of the Victory of Málaga (found at the end of the lesson plan)

- Color copies of the image for students to share, or the ability to project the image on a screen or wall

Standards

- Language Arts

- Collaboration

- Critical Thinking & Reasoning

- Information Literacy

- Invention

- Self-Direction

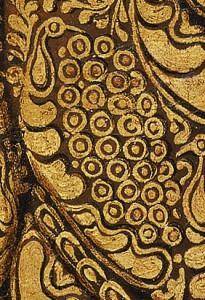

Virgin of the Victory of Málaga (Nuestra Señora de la Victoria de Málaga)

- unknown artist

This painting is attributed to Indian artist Luis Niño, a renowned painter, sculptor, and silver-worker born in Potosí, Bolivia. Niño worked directly for the Archbishop of Potosí and was so famous that his works were exported to Europe, Lima, and Buenos Aires. Two surviving paintings of the Lady of the Victory of Málaga [MAH-la-gah] are signed by Niño. This one may have been signed as well but, if so, the signature was lost when the painting was cut down at some point. However, the similarities between this painting and the others that were signed by Niño have led scholars to credit him for this one as well. In this painting of the Virgin of Málaga, Luis Niño has merged European and Indian artistic traditions and meanings into a unique and engaging work of art.

This is a painting of a statue of the Virgin of the Victory of Málaga, which resides in Málaga, Spain. Since Málaga is a port city, the Virgin is considered a patron of sailors, ships, and voyages. The original statue was a gift to the city. It depicts a seated Madonna, the mother of Christ in the Catholic tradition, with the Christ Child in her lap. As with many such statues across Spain, this statue was dressed in luxurious garments depicting the fashions of the time. The fabric of the Virgin’s dress makes it look as though she is standing instead of sitting. To cover the throne on which the Virgin sits, the garments were usually very wide, as seen in this painting. Engravings of the Virgin of Málaga were distributed widely in the New World and may have helped inspire Niño’s painting.

Details

Gold

The extraordinary use of gold decoration in this painting is exclusive to Cuzco, Peru, and the surrounding area, including Bolivia. Known assobredorado, or gold overlay in Spanish, the decoration was created by applying gold leaf over raised layers of gesso (primer paint). The highland areas were also known for weaving elegant textiles. The gold patterning on fabrics in this painting may reflect this reputation.

Wide Dress

The wide dress of the Virgin in the painting is similar to the actual wide cloth gowns that were used to dress statues of the Virgin in Spain. At the same time, the shape recalls the outline of the Inca earth-mother goddess, Pachamama, who often appeared in the shape of a mountain.

Dark Crescent Moon

The crescent moon at the feet of the Virgin symbolizes the Virgin’s Immaculate Conception. The moon shape is also reminiscent of the crescent-shaped tupu, or broach pins, that were (and still are) worn as fasteners for traditional Inca capes. When viewed in conjunction with the two vertical lines above the moon shape, the shape of a tumi (a ceremonial knife of the Inca and pre-Inca cultures of Peru and Bolivia) is formed. The tumi is a symbol of victory and conquest.

Birds

The Inca considered birds to be sacred creatures for their ability to fly and, consequently, to move closer to the sun god. Beautiful bird feathers were incorporated into clothing and headdresses of the Inca nobility and symbolized exalted status. Painters often incorporated bird feathers into images of the Virgin and Christ to indicate their sacred and honored position in colonial society.

Bottom of the Painting

The two scenes at the bottom of the painting depict a miracle performed by the Virgin of Málaga in the New World. The scene may show a rescue from a pirate attack, common along the west coast of South America in the 1700s. In the scene on the left, the Virgin of Málaga is seen in a cloud in the uppermost right corner. The miracle took place at sea, because we can see the mast and sail of a ship. We also know that this miracle occurred in the New World since the white flag with red X-shaped cross on one of the ships is the flag of Spain, but only in the New World.

Funding for object education resources provided by a grant from the Morgridge Family Foundation. Additional funding provided by the William Randolph Hearst Endowment for Education Programs, and Xcel Energy Foundation. We thank our colleagues at the University of Denver Morgridge College of Education.

The images on this page are intended for classroom use only and may not be reproduced for other reasons without the permission of the Denver Art Museum. This object may not currently be on display at the museum.