Students will listen to various sections of Petrarch’s poem “The Triumphs,” sketch images related to the text, and compare their drawings to the images portrayed in The Triumphs paintings. Students will analyze the paintings and critique the artist’s portrayal of the sections of the poem that they listened to. They will then create their own visual piece depicting a poem or song lyrics of their choice.

Students will be able to:

- feel comfortable drawing rough sketches without judging their work;

- understand and interpret sections of Petrarch’s poem;

- critique the artist’s choice of images in his portrayal of different items and concepts suggested in sections of Petrarch’s poem; and

- use their imaginations to create a work of art visually depicting concepts and images suggested by a written work.

Lesson

Day 1

- Warm-up: Have students think of their bedrooms and make some quick sketches of objects found in their room. Encourage them to think of little items as well as the overall layout. Tell them not to worry about the quality of the drawings but rather to focus on capturing what they see every day.

- Display The Triumphs paintings for the students to see. Tell them that the panels were most likely used to decorate a piece of furniture that would sit in the bedroom, where owners entertained visitors. Talk about who goes into their bedrooms; would they have important visitors there or in their parents’ bedroom? Why or why not?

- Choose and read aloud the following excerpt from Petrarch’s poem “The Triumphs” to the students. Ask them to make quick sketches of images that come to their minds as you read:

Four steeds I saw, whiter than whitest snow,

And on a fiery car a cruel youth

With bow in hand and arrows at his side.

No fear had he, nor armor wore, nor shield,

But on his shoulders he had two great wings

Of a thousand hues; his body was all bare.

And round about were mortals beyond count:

Some of them were but captives, some were slain,

And some were wounded by his pungent arrows.

- Ask the students to compare the images they drew while you were reading with those in the paintings. What did they pick out that was similar? What was different? How did the artist who created these paintings visually depict what Petrarch wrote? How did individual students choose to depict the poem?

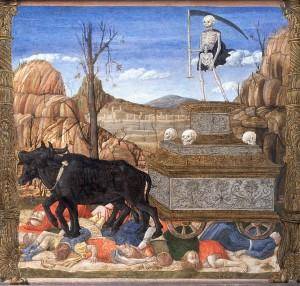

- Working in pairs, have students analyze the paintings carefully. Provide copies of the poem sections you read aloud. Invite the students to critique the artist’s portrayal of characters versus concepts, paying attention to foreground, background, large images, and small details. For example, in the Triumph of Death, the artist included a recognizable character of death with the skeleton, but also depicted the concept of death by portraying a barren landscape.

- For homework, have students select a poem or lyrics from a favorite song that they believe teaches an important lesson and bring them to class the next day. (If you have access to the Internet, you might allow students time in class to obtain their lyrics or poems.)

Day 2

- Warm-up: Play a song with very clear lyrics. Have students sketch out different images that come to mind as they listen to the song.

- Display The Triumphs again and review what you discussed in the previous lesson.

- Using the same concept the artist of The Triumphs used (depicting a sequence using a literary piece), allow students time to sketch out and then make a formal piece depicting the poem or lyrics they’ve brought to class. The formal piece may either be hand-drawn, a collage, or a combination of the two. Encourage the students to include both literal, character representations, and metaphorical, concept representations.

- At some point along the way, have students stop what they are doing and walk around to look at each other’s work. Encourage them to incorporate different techniques or images they like from their classmate’s work into their own work. Share that each piece will still look unique because each person will apply the technique or idea in their own way.

- Have students share their final pieces in groups of four, describing why they chose the images they did and how they depict a sequence.

Materials

- Paper or sketchbooks and pencil for each student

- Assorted magazines

- Scissors and glue or glue sticks

- Colored pencils, crayons, or washable markers

- CD player and a copy of a song with clear lyrics for warm-up on Day 2

- About the Art section on The Triumphs of Love, Chastity, and Death and the Triumphs of Fame, Time, and Divinity

- One color copy of the paintings for every four students, or the ability to project the image onto a wall or screen

Standards

- Visual Arts

- Invent and Discover to Create

- Observe and Learn to Comprehend

- Relate and Connect to Transfer

- Envision and Critique to Reflect

- Language Arts

- Oral Expression and Listening

- Research and Reasoning

- Writing and Composition

- Reading for All Purposes

- Collaboration

- Critical Thinking & Reasoning

- Information Literacy

- Invention

- Self-Direction

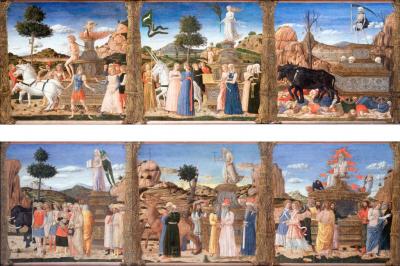

The Triumphs of Love, Chastity, and Death and the Triumphs of Fame, Time, and Divinity

Object: painting

Object ID: 1961.169.2

Medium/Technique

Oil on panel

Credit

Gift of the Samuel H. Kress Foundation

In Italy in the 1400s, art was a business like any other. People commissioned paintings from workshops, which were headed by master painters like Andrea Mantegna [mahn-TEN-ya] (1430–1506). Though it can be difficult to attribute paintings made in the workshop system to one artist, these paintings are attributed to Girolamo da Cremona.

We haven’t determined with certainty the original use of these panels, but one suggestion is that they adorned a piece of wedding furniture. The bride’s father or another male relative would have commissioned the paintings to decorate a cassone [kass-SO-nay], an elaborate chest for seating and storage of clothing, cloth, and jewelry. Cassoni (plural) often stood in bedrooms, where guests would be received, and fancy cassoni were intended to impress visitors with the family’s wealth. Paintings that were based on literary subjects, like these panels, were entertaining and also spoke well of the family’s education. Along with the message the paintings sent to visitors, they also reminded those who acquired such works how to live a Christian life. Other possibilities are that the panels decorated the sides of a bed platform, or that they might have adorned the walls of a Humanist’s studiolo (a scholar’s study or library).

Since wealthy patrons in the 1400s wanted paintings that would show off their aristocratic tastes, they liked to hire artists who were familiar with subjects inspired by ancient Greek and Roman literature and classical art of the past. The artist who painted these panels based them on a group of poems called “The Triumphs.” Though written by Italian poet Francesco Petrarch [fran-CHESS-co pet-TRARK] a century and a half earlier, his poems were still widely popular when these paintings were made. The poems allude to triumphal processions that passed through the Roman forum on their way to the Capitoline Hill, where the most sacred Roman temples were located. The processions consisted of marching men and prominent figures atop chariots pulled by four horses. The subject may have a dual significance in this case, as weddings of two powerful Renaissance families were also proclaimed “triumphs.”

These paintings can be read like comic strips, from left to right. They are not taken necessarily for face value, but rather for the allegorical meanings associated with their imagery. In the left-hand panel of the first painting, for example, Love rules over everyone—until in the second panel Chastity takes him prisoner. Chastity takes away Love’s bow and arrows and puts him in chains (see Cupid chained to the front of Chastity’s chariot in the middle panel). In the third panel, Death crushes everyone else under his wheels. But in the first panel of the second painting, Fame wins out over Death. Time, in the next panel, destroys Fame. And finally, Divinity triumphs over all. God sits on top of the last chariot. The underlying moral of the paintings is that, in the end, the only true hope for salvation is faith in God.

Details

Triumph of Love

Love’s chariot is surrounded by the captives of love, among them the Roman gods Jupiter, god of light and sky, and Mercury, god of trade, profit, merchants, and travelers. Behind the chariot are classic poets of love, Virgil and Dante among them. Love, hence, conquers all.

Triumph of Chastity

Chastity wears a white dress and carries a palm for victory. Unicorns pulling the chariot symbolize innocence. Cupid is now defeated and bound. Below Cupid are the virtues of Honesty, Shame, Reason, Modesty, Perseverance, and Glory.

Triumph of Death

Death crushes all beneath his wheels. The landscape is barren. Someone’s crown has rolled into the foreground showing that even the powerful are not spared.

Triumph of Fame

Fame holds the book of history. Around the chariot are heroes of Roman history. Also present is Judith, a biblical hero, holding the head of Holofernes [hall-oh-FAIR-knees], whom she killed to save Israel. Behind the chariot is a group of ancient philosophers led by Plato, Aristotle, and Pythagoras.

Triumph of Time

Father Time, who walks with the aid of a stick, is holding a “tau-cross” or “T” cross, alluding to the first letter of Theta, the word for God. He’s surrounded by old men in an arid landscape with the light of a setting sun.

Triumph of Divinity

God is surrounded by symbols of the four evangelists (Matthew = man/ angel, Mark = lion, Luke = ox, John = eagle). Red seraphim (the highest order of angels and fiery caretakers of God’s throne) flutter all around him, probably signaling divine inspiration. Around him are the apostles.

Comparisons Across the Panels

In each panel, compare the different beasts pulling the chariots, what each figure atop the chariot is holding, shapes and patterns on the chariots, trees and background scenery, and scene-framing rocks. Also note that God is the only seated figure.

Two Families’ Coats of Arms

To reinforce that these paintings mark the coming together of two powerful families, the artist included each family’s coat of arms. One probably belongs to the Gonzaga family, who at the time ruled the Duchy of Mantua where Mantegna’s workshop was based. Each coat of arms appears on a tower in the background—one in The Triumph of Chastity and one in The Triumph of Fame.

Changing Landscape

The landscape in the Chastity panel is very lush, green, and fertile looking, as opposed to the rocky barrenness in the neighboring Death panel. The variety of landscapes and the narrative detail within them helps set the tone in each scene. Deep landscape vistas also presented the opportunity for artists to demonstrate recent developments in conveying depth through perspective.

Funding for object education resources provided by a grant from the Morgridge Family Foundation. Additional funding provided by the William Randolph Hearst Endowment for Education Programs, and Xcel Energy Foundation. We thank our colleagues at the University of Denver Morgridge College of Education.

The images on this page are intended for classroom use only and may not be reproduced for other reasons without the permission of the Denver Art Museum. This object may not currently be on display at the museum.