Students will learn about how architect Daniel Libeskind draws inspiration for his work. Then, working in a similar manner, they will create their own architectural design sketches.

Students will be able to:

- investigate and debate issues of contemporary architecture that break accepted norms and give rise to new forms of artistic expression;

- relate local geographical features to the creation of a work of art; and

- articulate a personal philosophy for architectural design.

Lesson

Day 1

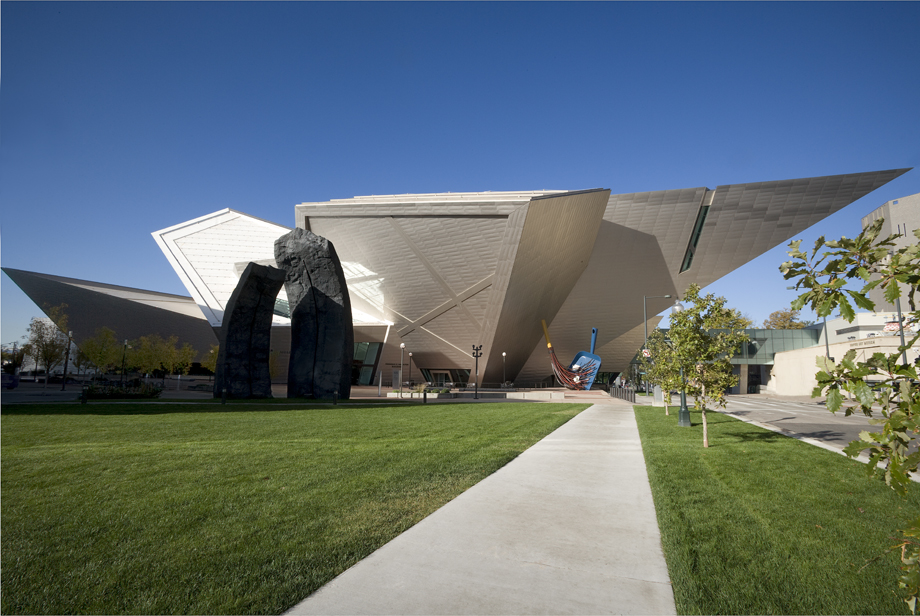

- Show students the image of the Frederic C. Hamilton Building designed by Daniel Libeskind and Davis Partnership Architects. Ask them if they have seen or visited this building before. If so, have students share their experiences. On YouTube there is a TED video clip of architect Daniel Libeskind describing his vision of architecture. He says that people “applaud the well-mannered box” but that he wishes to create something more, something that has “never existed before.” Ask students: Do you think he succeeded in applying this to the design of the Frederic C. Hamilton Building? Why or why not?

- Share information from the “Who Made It?,” “What Inspired It?,” and “Details” sections of About the Art. Discuss with students how the building was inspired by the local geography, particularly the Rocky Mountains. Do they see the inspiration of the Rocky Mountains in the design of the building? Where and how? Discuss how the unique structure of this building, with very few 90-degree walls, creates an interesting environment in which to hang art. You could show the image of Rain Has No Father? by El Anatsui. Point out that most of El Anatsui's artworks are hung on the 90-degree walls of other museums. The Frederic C. Hamilton Building’s slanted walls allow the shadow of the artwork to be a defining feature of its presentation.

- If time allows, show students the 18-minute TED video in which Libeskind describes his architectural philosophy and shows other examples of his work.

- Libeskind says that there are 17 words that inspire his architecture: unexpected, risky, memorable, communicative, optimism, raw, inexplicable, expressive, pointed, real, democratic, emotional, complex, political, radical, space, and hand. How can you see some of these things in the Frederic C. Hamilton Building? Where do you see “raw,” or “inexplicable”? What about the other words? How are they represented? For example, Libeskind explains "hand" with the phrase, “the computer follows the hand and not the hand follows the computer.” Ask students how they interpret what he might mean by this phrase?

- As a part of his design process, Libeskind also looks closely at the place in which the structure will be built. He finds inspiration in neighboring architecture, the location of the building, and the intended purpose of the building, among other factors. He then draws many sketches on paper. Once satisfied with the sketches, he puts the information into computer sketching programs. Explain to the students that they will work in a similar manner to sketch their own building design. Remind them that Libeskind’s architectural ideals are influenced by his 17 words. Ask students: What words have personal meaning to you? What words represent your identity? What words represent your view of the world? Tell students to make a list of all the words that are truly meaningful to them. Explain that the number of words is irrelevant, it is their identification with the words that counts.

Day 2

- Once the students have a list of inspirational words for their architectural designs, they should identify a site and a building type, and begin to sketch as they think about how and what to design. Ask them to think about the words they came up with. Ask them to consider whether they think buildings should reflect their personal identities. Is it possible to design a building that does not reflect you? Discuss the idea that buildings should serve people’s needs, capabilities, and desires, not just the architect’s personal interests and desires. How do you think you could balance form and function?

- Remind students that the Frederic C. Hamilton Building is influenced by the topography of the Rockies, the light, and the spirit of Denver. How do the surroundings, the purpose of the building, and other factors influence the overall design of the structure? Encourage students to think thoroughly about these questions. Prompt their thinking by asking them to describe in detail the ways in which this building may be used and the way people will act when inside. How will people arrive and what will they see/do when they enter? Why will they be coming to this building? Who will they be with? What kinds of needs do they have? Are they able-bodied? Are they young or old? Will they be trying to get from one place to another or will they be wandering? Do they visit with their friends and family? Are they alone, with a big group, or just with strangers? How does this thinking help you design?

- After creating a few rough sketches students should combine all of their planning into a more finished building design.

- When drawings are finished, have a gallery walk or art critique showcasing each student's design. Allow time for each artist to speak about his or her inspiration and process.

Materials

- About the Art section on the Frederic C. Hamilton Building

- Color copies of the Frederic C. Hamilton Building for students to share, or the ability to project the image onto a wall or screen

- If possible, the ability to project and play a digital film clip available here.

- Sketching and drawing paper

- Sketching and drawing tools

- Pens or pencils and paper for taking notes

Standards

- Social Studies

- Geography

- Understand geographic variables and how they affect people

- Visual Arts

- Invent and Discover to Create

- Observe and Learn to Comprehend

- Relate and Connect to Transfer

- Envision and Critique to Reflect

- Language Arts

- Oral Expression and Listening

- Research and Reasoning

- Writing and Composition

- Collaboration

- Critical Thinking & Reasoning

- Information Literacy

- Invention

- Self-Direction

Frederic C. Hamilton Building

Daniel Libeskind and Davis Partnership Architects, United States

2006

146,000 sq. ft.

Photo by Jeff Wells, Courtesy of the Denver Art Museum

Photograph © Denver Art Museum 2009. All Rights Reserved.

Architect Daniel Libeskind worked with Denver-based Davis Partnership Architects to design the Denver Art Museum’s Frederic C. Hamilton Building.

Libeskind was born in Poland in 1946, the son of two Holocaust survivors. At the age of eleven, he immigrated to Israel with his parents, where his family lived for two years before they left for New York. Libeskind was one of the last immigrants to arrive by boat through Ellis Island and he became an American citizen in 1965.

As a child Libeskind was a musical prodigy, winning international competitions with his performances on the accordion. He left music to study architecture at New York’s Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art, followed by graduate work at Essex University in England. He went on to work as a professor and theorist before completing his first commission, Berlin’s Jewish Museum, at the age of fifty-two.

The Denver Art Museum’s Hamilton Building is Libeskind’s first completed building in the United States. He was also chosen as the master plan architect for the World Trade Center site in New York City.

In 1999, museum director Lewis Sharp and then-mayor Wellington Webb decided it was time for the museum to expand. A new building would allow the DAM to display more of its world-class collection and provide the space needed to host major traveling exhibitions.

With the Hamilton Building, Daniel Libeskind continued a tradition of bold architecture that began with Gio Ponti’s North Building. Libeskind tells us that he was inspired by the “craggy cliffs of the Rockies” and by his experiences in Denver. He describes Denver as “a dynamic place, the people are dynamic. And that is part of the composition of the building.” The lively architecture signals to the public that new things are going on inside; the experience begins before one even enters the DAM.

Details

Titanium

Libeskind chose to complement Gio Ponti’s million gray glass tiles of the North Building by selecting another reflective and unusual material: 9,000 titanium panels. Libeskind said, “We had an aim from the beginning: a building that is luminous.” The Hamilton Building’s different sides reflect light at different angles, and thus appear to be different shades of gray. The titanium also reflects varying colors throughout the day. It often appears more rosy in the early morning hours and golden at sunset, depending on the weather.

Fun Fact: 9,000 titanium panels cover the building’s surface.

The Prow

The tip of the building, which we call the “prow,” makes a reaching gesture across 13th Avenue toward the North Building and Civic Center. The angled walls of the prow, and the many other angled walls that shape the building, are reflected inside and create unique interior spaces. These dramatic spaces have provided new opportunities for innovative displays of artwork.

The Atrium

Libeskind spoke of the atrium as an introduction to the visitor’s experience of the building: “The first sounds, the atmosphere, the connectivity with that atmosphere—the mood is set. And I think it’s proper that an atrium should set those moods because that’s where you quite literally enter, get informed, get ready for an adventure with art.” The walls and ceiling of the atrium create a variety of shaped spaces, making it one of the most dramatic spaces in the building.

How Does the Building Stay Up?

The building is essentially a giant truss, meaning its steel frame is a balanced network of interlocking triangles. After all the steel beams are set in place, the building holds itself up and transfers weight to “anchors” of concrete pillars that reach down into bedrock. Libeskind described the building as a tree, branching out from these anchoring “roots.”

Fun Fact: 2,750 tons of steel and 50,000 steel bolts were used in the Hamilton Building.

Funding for object education resources provided by a grant from the Morgridge Family Foundation. Additional funding provided by the William Randolph Hearst Endowment for Education Programs, and Xcel Energy Foundation. We thank our colleagues at the University of Denver Morgridge College of Education.

The images on this page are intended for classroom use only and may not be reproduced for other reasons without the permission of the Denver Art Museum. This object may not currently be on display at the museum.