My garden is my most beautiful masterpiece.

April has arrived! As last month’s blog demonstrated, I am enthusiastically welcoming the onset of warmer weather and, with it, the growing season. If the gardens surrounding Monet’s home in Giverny are any indication, this is a sentiment I am certain the artist shared. For avid gardeners like Monet and myself, April means we can begin planning the year’s garden, starting seeds indoors, and preparing the ground for early and late spring plantings. As we begin preparing for the growing season, let’s seek inspiration from Monet’s incredible Giverny gardens.

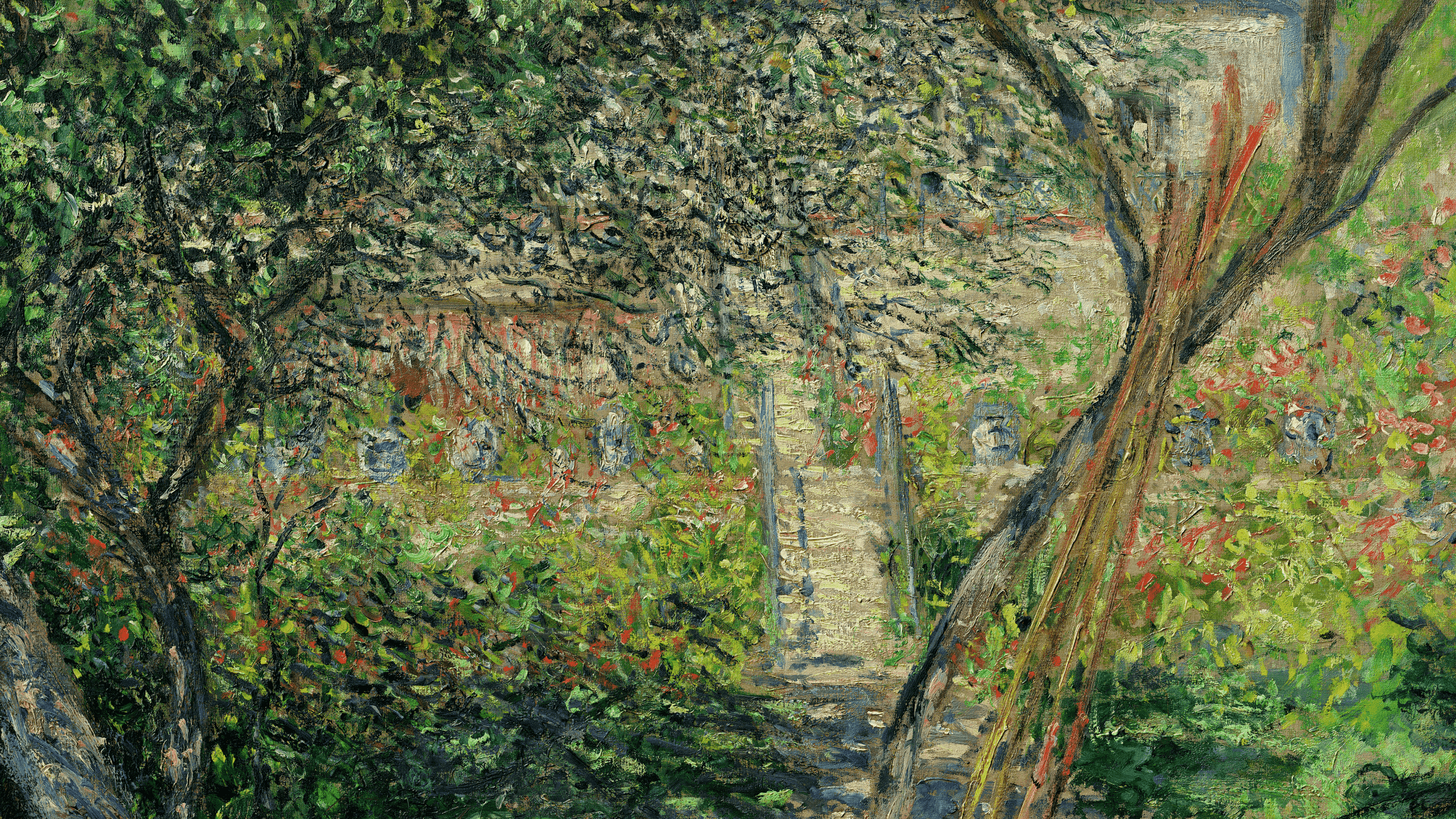

The Garden at Vétheuil (Le Jardin de Vétheuil), 1881. Private collection.

Gardening was central to Monet’s life, even before he moved to Giverny in 1883, as The Garden at Véteuil demonstrates (With this painting, Monet captured a view of the garden at his Vétheuil residence. You can see this canvas in person, as well as the first painting Monet ever made of his Giverny garden, when the exhibition opens in October 2019!).

But it was not until he arrived in Giverny that he began gardening on an unprecedented scale, hiring a team of gardeners to assist his pursuits. Monet’s property was expansive and covered in gardens of all styles, though they can be divided into three categories: The flower gardens surrounding Monet’s home, the water garden located across the street, and his 2.5 acre potager (vegetable garden).

Creative Commons usage from Flickr

Flower Gardens

Monet loved flowers of all kinds, and his flower garden comprises many different beds. Among the most famous are those that line the pathway–or Grand Allée, as it’s called in French–that leads from the road to his home. In those, he planted a number of different varieties, including vining nasturtiums that crawled along the path’s edges and climbing roses trellised above on large green arches. Monet also used a number of rectangular, raised flowerbeds to experiment with color and texture pairings that would inform his paintings.

Fifty-three beds were devoted to monochromatic and polychromatic plantings, which are referred to as his paintbox beds. These beds included roses, clematis, poppies, marigolds, bearded irises (There’s even a variety named ‘Iris Mme. Claude Monet!), tulips, forget-me-nots, sunflowers, pansies, azalea bushes, alliums, peonies, rhododendron, foxgloves, snapdragons and daffodils, among others. In addition to informing his paintings, these beds provided cut flowers for each room in his home, and his tastes ranged from simple bouquets involving just one flower variety, like sunflowers or white clematis, to more elaborate arrangements involving different varieties. He also collected orchids, which he grew in his property’s greenhouses.

April will be here and Monet will refuse to budge [from his garden].

Creative Commons on Flickr

Water Garden

Upon his arrival in Giverny in 1883, Monet quickly began to adjust his property. It was not until 1895, however, that he won municipal approval to commission a pond on his land by diverting water from the Epte Tributary. This manufactured body of water was greatly influenced by Japanese garden design, reflecting his ardent interest in contemporary Japanese woodblock prints and creating the ideal conditions for his creative pursuits, which included his celebrated waterlilies paintings. In addition to the exotic waterlilies in his pond, Monet grew willows, roses on arches, peonies, bamboo, and wisteria along meandering pathways and Japanese-style bridges. The resulting garden is one of Monet’s most enduring legacies.

Le Potager (Vegetable Garden)

Monet’s kitchen garden, or potager in French, was located a short distance from his property. It was surrounded by peonies for cutting and divided into different plots according to plant families: the cabbage family, which included hardy radishes, kale, and turnips; legumes, such as peas and beans; and tender vegetables, like tomatoes, peppers, potatoes, and eggplants. To keep the soil fertile, Monet’s team of gardeners practiced crop rotation, so that one plant family never occupied the same area for two successive seasons. He also grew onions, endive, beets, parsnips, carrots, zucchini, celery, rhubarb, asparagus, artichokes, melons, cucumbers, garlic, shallots, and cabbage. The potager provided food for his large family nearly year-round.

Overall, there are many corollaries between Monet’s approach to painting and gardening. Just as he contributed to the development of the ‘new’ and avant-garde impressionist style of painting, he was known for experimenting with new and foreign plant varieties. He was the first to grow exotic waterlilies in the region, which were so unknown to his neighbors that they worried the lilies would poison the tributary connected to his pond. He was also the first person in the area to introduce Chinese artichokes in his potager.

Monet's Gardens Still Grow

For me, the most special aspect of Monet’s gardens is that they are still growing today, preserved for posterity and the nearly 630,000 visitors, who arrive each year to immerse themselves in Monet’s world—one that was carefully perfected over the last 43 years of his life. Vivian Russell says it best: “Monet will never paint again, and his canvases will never change. But the garden rising as new every year from the bare earth loses none of its wonder.”

In our May Monet Moment I'll provide some suggestions for creating your own Monet garden.