Students will view the painting Wind River Country by Albert Bierstadt and discuss his motivation and process for creating majestic landscape paintings. Working in a similar style, students will create collaborative mural paintings of a fantastic landscape.

Students will be able to:

- identify realistic and exaggerated elements in visual information;

- hypothesize and discuss how choice of artistic design and elements help portray artistic intent and meaning in a work of art;

- compile various images of landscape and natural elements as possible inspiration for a work of art; and

- successfully collaborate and work in groups to create a landscape design and large mural painting.

Lesson

Day 1

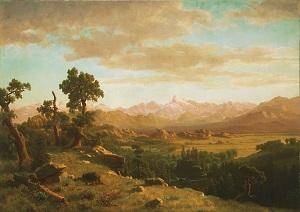

- Show students the image of Wind River Country and ask them if it reminds them of anywhere they have been or seen before? Why? What things remind them of a place they have been or seen (e.g., rocks, trees, mountains, the sky, etc.)? Where is this place that they remember? Are there things in this painting that are a little different from where they were? Does Wind River Country look like a place they would like to go? Why or why not?

- Share with students information from the About the Art section and explain that the artist Albert Bierstadt traveled to the Rockies from New York in the mid-1800s as a member of an expedition that explored Western lands. This painting was inspired by the Wind River mountain range that he saw in western Wyoming. When the trip was over he brought back photographs, sketches, notes, and specimens to his studio, and used them to compose large landscape paintings that showed the grandeur of the American West to people who had not seen it. But he didn’t paint it exactly like it was; he exaggerated to show people how big and majestic the land seemed to him.

- Show students the "Details" portion of the About the Art section and point out ways that Bierstadt used a combination of realistic and exaggerated imagery to give viewers a sense of the wide expanses and majestic mountains that he encountered in the West. He really wanted people to understand how fantastic the American West was, and he made his landscape paintings very large and dramatic. Sometimes he would even have showings of his paintings where he would use theatrical lighting and have viewers look at his paintings through opera glasses to give them the feeling that they were seeing a play or a show rather than looking at a flat painting.

- Tell students that they will work in groups of 4 or 5 to compile landscape images that they cut from magazines, old calendars, or photographs they bring from home to use as inspiration for a new landscape design.

Day 2

- Rather than creating a collage with the gathered images, students will use them as inspiration to sketch a new composition and fantastic landscape design on sketch paper, making sure that elements of their composition (rocks, trees, animals, or whatever they have found) are distributed in the background, middle ground, and foreground.

- Then they will transfer and enlarge their sketch on large pieces of butcher roll paper that are the same size as Wind River Country—or even larger. Sometimes Bierstadt painted canvases up to nine feet!

Day 3

- Students can add color to their large group mural using paint, crayons, or whatever medium is best for the purposes of the class. Remind students to use appropriate craftsmanship and to follow all rules for supplies and clean up.

Day 4

- Once each group is finished, you could have a showing of each mural using spotlights or flashlights, maybe even presenting the artwork in the school cafeteria or on a stage. Provide the audience with opera-type glasses or plastic binoculars found at inexpensive toy stores such as US Toy, or perhaps paper glasses cut from a copied template.

- As a class, discuss how all of the landscapes look. Remind students that Bierstadt’s paintings were meant to awe the viewers back east. Have the student audience describe the group murals that are on display, and discuss whether they give viewers the same feeling.

Materials

- About the Art section on Wind River Country

- Color copies of Wind River Country for students to share or the ability to project the image onto a wall or screen

- Magazines or calendars with landscape images, or access to photographs of various landscape scenes

- Scissors

- Folders or envelopes in which to keep gathered images

- Sketch paper

- Pencils

- Large rolls of butcher paper

- Paint, brushes, and water containers

- Opera glasses, plastic binoculars, or paper glasses

- Access to a stage, cafeteria, or other area to display student murals and hold a discussion of the works

Standards

- Social Studies

- History

- Geography

- Become familiar with United States historical eras, groups, individuals and themes

- Understand people and their relationship with geography and their environment

- Visual Arts

- Invent and Discover to Create

- Observe and Learn to Comprehend

- Relate and Connect to Transfer

- Envision and Critique to Reflect

- Language Arts

- Oral Expression and Listening

- Research and Reasoning

- Collaboration

- Critical Thinking & Reasoning

- Information Literacy

- Invention

- Self-Direction

Wind River Country

- Albert Bierstadt, American, 1830-1902

- Born: Solingen, Germany

Albert Bierstadt was born in Solingen, Germany in 1830, and was brought to New York at the age of two. He returned to Germany when he was twenty-one years old to study at the Düsseldorf Academy. Eight years later, in 1859, Bierstadt made his first trip to the Rocky Mountains when he joined a government expedition led by Colonel Frederick W. Lander (for whom Lander, Wyoming was named). Following this trip, he opened a studio in New York, where he drew from his sketches, photographs, specimens, and Indian artifacts to create large landscape paintings. Through his artwork, Bierstadt introduced Easterners to the scenery of the Rockies. While still in his early thirties, Bierstadt became one of the most successful and highly paid painters in the United States.

The Wind River Range is part of the Rocky Mountains, located in western Wyoming. Bierstadt identified the river here as the Sweetwater River, and the prominent mountain as Fremont’s Peak, known today as Temple Peak. Bierstadt liked the Wind River area enough to return there after he left the Lander expedition. As one of America’s early artist-explorers, he was looking for personal adventure and hoping to establish his artistic “territory.” The Wind River area is the subject of many of his works. Around the time Wind River Country was painted (1860), interest in the American West had reached a high point. This was in part due to western movement along the Oregon Trail; and to the writers, artists, and surveyors who had reported on the region over the past thirty years. Interest in finding American landscapes that would rival the European Alps was also growing. Bierstadt’s paintings satisfied on both counts—they delivered both heightened grandeur and specific details and places.

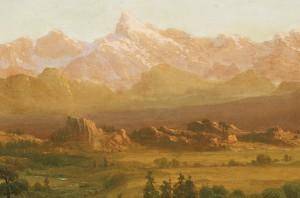

Details

Scale

Bierstadt liked the theatricality of a large painting. Wind River Country measures 42 ½” wide x 30 ½” tall, and some of his later pictures were four times that size. Sometimes, Bierstadt would show his work on a stage with dramatic lighting and viewers could pay admission to look at the painting with opera glasses.

Sense of Depth

Bierstadt was very interested in early photography, shooting photos on his journeys west that he could view through a stereoscope for a three-dimensional effect. Working with photographic source material in his studio may have contributed to Bierstadt’s convincing illusion of space. Looking at the mountains we can see clearly that some are close to our vantage point, while others are far away.

Light & Dark

Warm colors highlight areas touched by the sun. The viewer’s eyes are drawn to lighter areas, particularly the mountains in the distance.

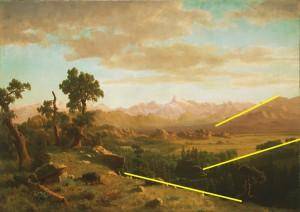

Composition

Bierstadt guides the viewer through the painting by arranging elements of the scenery along diagonal lines.

Details

The foreground is full of details—carefully rendered foliage, rocks, a hollow log. In his studio, Bierstadt drew from multiple field sketches and photos to compose a pleasing picture. The scene we see here is a composite view, not an individual scene that the artist witnessed.

No Reference to Humans or Civilization

We see nature here as untouched by humans. The landscape appears rather inaccessible; there is no clear way one would be able to navigate through the scene.

Rawness of Nature

The image of a grizzly bear feeding on an antelope contributes to the sense of scale and adds drama to the scene.

The Highest Peak

Bierstadt uses several pictorial techniques to suggest the importance of the distant peak. It is placed only slightly off-center, and has framing elements on all sides—trees, clouds, and the darker mountains in front of it are parted aside. The hazy air makes the peak lighter and brighter.

Funding for object education resources provided by a grant from the Morgridge Family Foundation. Additional funding provided by the William Randolph Hearst Endowment for Education Programs, and Xcel Energy Foundation. We thank our colleagues at the University of Denver Morgridge College of Education.

The images on this page are intended for classroom use only and may not be reproduced for other reasons without the permission of the Denver Art Museum. This object may not currently be on display at the museum.