Students will use Phillip Guston’s painting Blue Water as inspiration for creating an “image portrait” of a historical figure, arranging images that reflect qualities, actions, and characteristics of the figure into a composition.

Students will be able to:

- describe the themes of Blue Water and articulate the role of Guston’s visual alphabet of symbols;

- summarize, in a list of key words, a historical figure’s actions, choices, impact, etc.; and

- represent the figure’s actions, choices, impact, and other traits in an "image portrait," considering chronology, contradictions, and any other influential factors.

Lesson

Day 1

- Preparation: Read the About the Art section on Blue Water.

- Warm-up: Lead a group discussion about Blue Water. Talk about Guston’s “new alphabet” and his approach to telling a through images and symbols drawn from his life experiences.

- Ask students to consider how they could use this idea to describe a historical figure they have been studying.

- Divide students into small groups and ask them to collectively generate 20 words that describe the life of the historical figure. Optional: Designate categories under which to brainstorm these words. Examples of categories might include: key actions, key life experiences, personality traits, physical characteristics, impact.

- Once each group has come up with 20 words, have them review the list and distill it to the 10 most important words that reflect the historical figure.

- Ask the groups to discuss each word in relation to the figure’s life and decide upon an appropriate image, symbol, or treatment of the written word to represent the meaning of each word.

- Have students work with their groups to place their chosen symbols and images in an overall composition that best creates a portrait of the figure. Ask them to consider chronology, contradictions, and other relationships.

- Hang the completed portraits on the classroom wall.

Day 2

- Preparation: Number each portrait for ease of reference during the class discussion.

- Lead a discussion in which students compare and contrast portraits and discuss how each portrait depicts the historical figure.

Materials

- Materials for researching historical figures related to history unit the class has been studying

- Source material for image collection: magazines, newspapers, Internet and printer, etc.

- Journal

- White paper or computer software for creating "image portrait" of historical figure

- About the Art section on Blue Water

- Color copies of Blue Water for students to share, or ability to project the image onto a wall or screen

Standards

- Social Studies

- History

- Evaluate and analyze sources using historical method of inquiry and defend their conclusions

- Visual Arts

- Observe and Learn to Comprehend

- Relate and Connect to Transfer

- Language Arts

- Oral Expression and Listening

- Research and Reasoning

- Writing and Composition

- Reading for All Purposes

- Collaboration

- Critical Thinking & Reasoning

- Invention

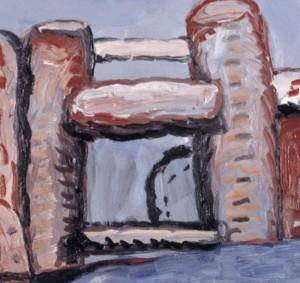

Blue Water

- Philip Guston, American, 1913-1980

- Born: Montreal, Canada

- Work Locations: New York

Philip Guston (originally Philip Goldstein) was born in Montreal, Canada, in 1913 and moved to California when he was six. He began his professional art career in the 1930s, painting murals with social and political themes. In the 1950s, Guston began creating non-representational art (art with no recognizable subject matter), for which he became widely known and respected. After creating this kind of art for nearly two decades, Guston shocked the art world in the late 1960s when he abruptly abandoned non-representational art and started filling his new paintings with objects like eyes, cigarettes, and soles of shoes. “I got sick and tired of all that purity. I wanted to tell stories,” he said. However, the stories in Guston’s paintings weren’t always crystal clear; some of the shapes that he painted resembled real-world objects without being totally recognizable. He wanted “to paint the world as if it had never been seen before, for the first time…”

Guston worked with no master plan, and repeatedly expressed astonishment at the forms created by his own paintbrush. “I am a night painter,” he said. “So when I come into the studio in the next morning the delirium is over. I come into the studio very fearfully… And the feeling is one of, ‘My God, did I do that?’” Late in his life, Guston became completely immersed in his art. He would paint around the clock, working for more than 24 hours at a time. He wrote, “[My paintings] are large, ten feet or so, and take complete possession of me… It is a new “real world” now that I am making—I can’t stop.” Guston died in 1980 in Woodstock, New York.

“The trouble with recognizable art is that it excludes too much. I want my work to include more…I am therefore driven to scrape out the recognition…to erase it. I am nowhere until I have reduced it to semi-recognition,” Guston said. Around 1970, Guston began assembling what he called his “new alphabet”: a set of forms or shapes, mostly objects from his own life experiences, some of which actually looked like letters. Cigarettes (Guston was a chain smoker his whole life), light bulbs, body parts, and soles of shoes began crowding his compositions. These autobiographical forms shared the space with other less recognizable forms, whose origins were sometimes unclear even to the creator himself. Speaking of the forms that comprised his “new alphabet,” Guston said, “Sometimes I know what they are, but if I think ‘head’ while I’m doing it, it becomes a mess…I want to end with something that will baffle me.”

Another source of inspiration comes directly from Guston’s childhood. On his thirteenth birthday, Guston’s mother enrolled him in a correspondence course at the Cleveland School of Cartooning, a fitting gift for the boy who was a fan of newspaper comic strips Krazy Kat and Mutt and Jeff. However, Guston soon grew bored with the drawing lessons and gave up after taking only a few courses. In his mid-50s, Guston returned to his earliest inspiration. Many of his late paintings—like Blue Water—borrowed their style from the cartoons he loved as a boy.

Details

Color

Guston used a very limited color palette for this piece: only blue, red, white, and black.

Cartoon Quality

The cluster of objects floating on top of the water strikes some viewers as cartoon-like. Notice the bold outlines, the simplified colors, and the rounded edges.

Large Eye

At the far right end of the cluster of shapes, a large eye looks back at the other forms. Sonnet Hanson, DAM Master Teacher for Modern and Contemporary Art, poses the question, “If one sees the eye as that of the artist, could it be that in some way he is looking back on the remnants or unsettling events of his life?” Other critics purport that Guston did in fact depict himself as a Cyclops or a Cyclops eye in more than one painting.

“Semi-recognizable” Shapes

The ambiguous shapes in this painting are a part of what Guston called his “new alphabet.” Some forms are recognizable and some are not. Is that a ladder, or a letter? Is that a horseshoe or the sole of a shoe? Are those legs sticking out of the water, or intestines? Guston didn’t set out to create a clear-cut meaning for his paintings, so the possible interpretations are endless.

Funding for object education resources provided by a grant from the Morgridge Family Foundation. Additional funding provided by the William Randolph Hearst Endowment for Education Programs, and Xcel Energy Foundation. We thank our colleagues at the University of Denver Morgridge College of Education.

The images on this page are intended for classroom use only and may not be reproduced for other reasons without the permission of the Denver Art Museum. This object may not currently be on display at the museum.