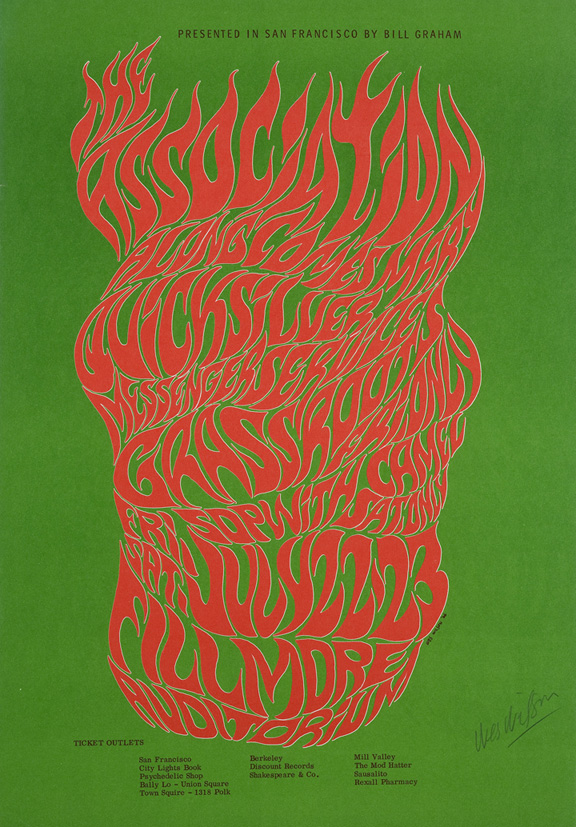

Students will discuss how Wes Wilson’s poster Association, Quicksilver Messenger Service, Fillmore Auditorium, San Francisco reflects the time and place in which he created it and how this type of artistic expression continues to inform and influence a wide variety of visual media today. Students will also examine how the form differs from images prevalent today and design their own lettering style and posters to attract a specific audience of their choosing.

Students will be able to:

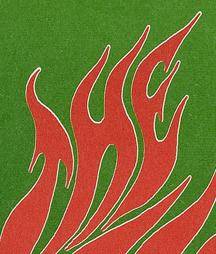

- identify the impact of shape and color in Wes Wilson’s poster in communicating a specific message to a target audience;

- describe how the psychedelic art form informs images they see today;

- discuss how advertisers use images to influence a particular audience; and

- feel comfortable enough to create their own posters to the best of their ability.

Lesson

- Warm-up: Play music from some of the bands advertised in the poster. Ask students if they know from what time period the music comes. How do they know? If you had to advertise that music, what type of image would you create? Allow them use colored pencils to sketch out some ideas.

- Share the poster. Compare to their pieces and discuss similarities and differences. How does the poster reflect the music and time period? How do they know? What is the impact of the lettering and colors? Wilson broke all the rules of advertising at the time to express himself but also to appeal to his intended audience, and it worked! Tell students that people would take the posters off walls and phone poles. Why do they think people would do so?

- What would happen if this type of art form had not occurred? What things might they not see today?

- Looking at the poster, ask if they need to know what it’s communicating to be drawn to it? What would draw them and people they know to a poster today? Using only lettering?

- Have students pick an event (either a real future event or something from their imagination) and imagine the intended audience. Have them create their own posters using only lettering and colors for both the artistic and communicative value of the poster.

- Share in groups or with the entire class.

Materials

- Music from the bands listed on the poster and a CD or tape player. The bands are as follows:

- The Association

- Along Comes Mary

- Quicksilver

- Messenger Service

- Grassroots

- 11x14 or 11x17 sheets of paper (2-3 for every student – to allow for mistakes)

- Colored pencils or markers

- 1 color copy of the poster for every 4 students, or the ability to project the image onto a wall or screen

Standards

- Visual Arts

- Invent and Discover to Create

- Observe and Learn to Comprehend

- Relate and Connect to Transfer

- Envision and Critique to Reflect

- Language Arts

- Oral Expression and Listening

- Research and Reasoning

- Writing and Composition

- Reading for All Purposes

- Collaboration

- Critical Thinking & Reasoning

- Information Literacy

- Invention

- Self-Direction

Association, Quicksilver Messenger Service, Fillmore Auditorium, San Francisco

Wes Wilson, United States

1966

20 1/8 in. x 14 1/4 in.

Partial gift of David and Sheryl Tippit; partial purchase with Marion G. Hendrie Fund; Florence & Ralph Burgess Trust; and other Denver Art Museum funds, 2009.515

© 1966 Wes Wilson

Wes Wilson was born in Sacramento, California in 1937. He got his start while working for a print shop in San Francisco, where he designed posters and handbills for early dance concerts. During the 1960s, he became the first artist to consistently create posters for the two main concert promoters on the San Francisco music scene-Bill Graham, who produced concerts at the Fillmore Auditorium and Chet Helms, who ran the Avalon Ballroom. One of the first projects to bring Wilson recognition was a handbill for the legendary Trips Festival, a three-day event that took place in San Francisco and set the stage for later dance concerts.

Wilson initially produced as many as six posters a month for the Fillmore and the Avalon. In 1966, when the pressure of designing multiple posters each week became overwhelming, he began working solely for Bill Graham. While Chet Helms loved to contribute to the poster-making process, Graham allowed Wilson the artistic freedom he desired. "Chet almost always had the theme already picked out, but with Bill, you could do your own thing, mainly because he was too busy to deal with you. He liked that I could do posters without him having to tell me anything." Despite the freedom that came with working for Graham, Wilson began to feel exploited and stopped producing posters for the Fillmore in 1967. Although Graham was building an increasingly profitable poster-selling enterprise, Wilson was paid only $100 per poster, without royalties. Wilson continued to produce posters for other venues, including the Avalon Ballroom. Today he creates artworks from his farm in the Missouri Ozarks.

Psychedelic posters were originally created as advertisements for dance concerts that took place in San Francisco from 1965 to 1971. The term "psychedelic" comes from the Greek psyche (mind) and deloun (make visible or reveal), and refers to the mind-altering effects of LSD, a hallucinogenic drug that was frequently used at these events. Designs for concert posters were a visual reflection of the experiences one might have at a dance concert. The movement, colors, and images all reflect the kinds of things that would appeal to a concertgoer's many senses. Posters were plastered on telephone poles and in store windows, and were often stolen by people who took them home to hang on their walls or refrigerators. "It was very disconcerting to poster a whole street and then walk back a few minutes later and discover that 90 percent had been removed. But I soon learned that a stolen poster carried home and pasted on a refrigerator reached the audience I wanted," said Helms.

Wilson was a part of the counter-culture that he was trying to reach out to, and was inspired by his personal experiences. "I imagine the posters were like some kind of imprint like a section of my mind at that time. And some of them were pretty weird, pretty strange," said Wilson. His designs set the style, capturing the full sensory experience of the dancehall environment and the visual distortions brought on by psychedelic drugs.

Details

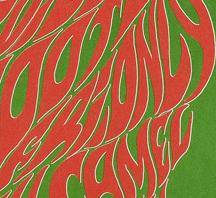

Semi-Legible Text

Psychedelic posterslike this one were often filled with text that was difficult to read. “Well, it’s nice, but I can’t read it,” Bill Graham said about one of Wes Wilson’s poster designs. The artist replied, “Yeah, and that’s why people are gonna’ stop and look at it.” Wilson proved right. People often spent time looking at the posters and would actually sway back and forth as they tried “to follow the curvature of the words, the lettering,” noted Graham.

Lettering

Wilson drew his letters by hand to create three-dimensional, undulating shapes. This lettering style became characteristic of his early work. “I like to do my work freehand—no ruler and stuff. Just make it fit naturally. If I needed to make a letter a little wider, well, I would.”

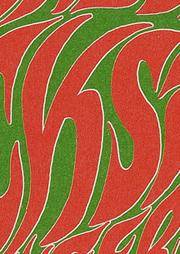

Color

Wilson used “loud” or very bright colors to reflect the dancehall atmosphere. By placing the bright red and green next to each other, he created forms that seem to vibrate.

Movement

Wilson formed each letter so that it fit into the overall shape of the flames. The flowing lines evoke the energy and movement of the dancing crowd and the light shows that one would see at a concert.

Funding for object education resources provided by a grant from the Morgridge Family Foundation. Additional funding provided by the William Randolph Hearst Endowment for Education Programs, and Xcel Energy Foundation. We thank our colleagues at the University of Denver Morgridge College of Education.

The images on this page are intended for classroom use only and may not be reproduced for other reasons without the permission of the Denver Art Museum. This object may not currently be on display at the museum.